Demise or Absolution

If we were in the 70s, we would call Éva Mayer a 'committed' artist. At that time there was a strongly positive value attached to this adjective. It was used for artists who discuss sensitive social or political problems in their works or base the core of their oeuvre on such issues. Although the word is not used anymore, things have not changed. Artistic sensitivity still steps into the field of themes outside of questions concerning private life, as human problems that affect a wide range of people are present today as well. Problems that we openly and freely discuss as well as problems that we mention tentatively and implicitly as they are taboos, topics of unknown fields.

In case of our female artists it is not a widespread behaviour or way of thinking to discuss 'daring' community topics in art, as in our society, in social circles the outdated, patriarchal idea that a woman's place is in the kitchen or at the cradle creating a supplementary world that complements that of men is still prevailing. Speaking of cradles we should refer to Mayer's previous installation shown in church setting presented in Limes Gallery of Komárom together with Áron Majoros. This installation revolved around questions regarding female infertility, and in the exhibiting space she placed cradles with art prints lying in them.

Mayer does not only approach sacral but also desacral spaces with special sensitivity both in theoretical and practical sense. Through international examples in her doctoral essay she examines possible contemporary art uses of sanctuaries still having or having already lost their original function. She tried to find what role desacralised spaces used for art purposes may have on defining Central and Eastern European identity, and how much influence the reuse of ex-churches may have on the communal and religious life of a community.

Mayer is a well-rounded artist, she analyses her main themes from diverse perspectives in a systematised way. She has long been addressing issues about the life of religious buildings. We mostly use 'life' for human beings, but I have been convinced in the previous decades that sanctuaries can also tell their life stories about the storm of history. In the 80s when travelling from Novi Sad to Zagreb I was shocked by the fresh ruins of Orthodox churches, in the 90s I witnessed how a contemporary theatre company moved into the former synagogue of Subotica causing damage in the building due to the lack of respect towards its aura. I have also encountered very different examples for instance in the case of the synagogue of Somorin. Also, based on the video on Mayer's exhibition in Komárom it can be seen that simultaneously with the new function the local Calvinist church was also filled with spirit, sacrality. Even though this spirit is not present in its original nature, but as a poetic quality, which is also occasionally characterised by majestic values.

When perceiving the works of 'Doom and Purification' one switches from thinking of the life of religious buildings to worrying, as the pieces on view evoke the tremendous feeling of concern. 'Life is fundamentally tragical' says Borisz Paszter, Russian poet and writer. It is a valid recognition by someone who experienced the feeling himself together with numerous others of his kind under the Soviet dictatorship. Mayer's works place this experience into focus, and extend the concept of human tragedy with architectural objects that humans built to praise God.

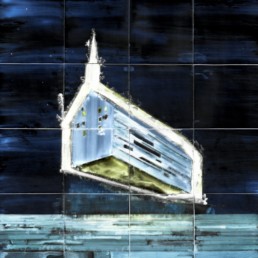

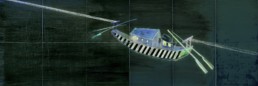

The end of sanctuaries is also the loss of cultures or even the disappearance of them. As a temple is always more than an institution serving the church. They are often artworks themselves capturing an age or an entire human culture. Although television has widely spread the visual drama of the destruction of churches with its reports, Mayer's works provide the experienxe of a real trembling feeling of perceiving terror. Regardless of all this it has to be stated that the pieces on show are beautiful, with overwhelming impact on the viewer, proving that even tragedy can be depicted with dignity. It is of curiosity that the artist creates the phenomenon of levitation by 'pulling' the builiding out of the soil at points. The temples floating above the ground resemble the spirit breaking through the human body without having a determined path in the future.

Being electographers we are curious to know what technological tricks helped the artist to create this otherworldly atmosphere. It is clear that they are not the graphic programme of the computer that enabled this invention of visual language to happen. The method must have been more complex with an artistic approach from a more visceral level.

Mayer uses traditional watercolour technique to paint on glass sheets which are later scanned. The aquarelle pieces are deeply transformed when being digitally captured. The colours are turned into their negatives, which process can be continued further to reach a final visual composition. I think that such further manipulation of the images must be limited as the exhibiting space requires rough simplicity which has a striking impact. Simple solutions are always stronger that overdone artificial sophistication.

Éva Mayer addresses the question 'Doom or purification?', which cannot be answered with a unified, homogenous reply. It cannot be answered, because the concepts do not exclude each other. Fire may create new life. It is not a coincidence that purification includes the word 'pure'. Rottenness, sins, malicious intentions, lies and other similar categories can only be eliminated by fire. Also, death contains the possibility of resurrection. Therefore, the answer is both doom and purification. However, only until humans can reproduce themselves.

Bálint Szombathy

Opening speech of Éva Mayer's exhibition entitled 'Death or Purification', MET Galéria, Budapest, 2019. május 9.

*The title of the thesis: Reusing Sacral and Desacralised Spaces with Respect to Contemporary Art, Religion, Central and Eastern European Identity with Special Focus on Slovakia